Suicide rates linked to cigarette taxes, smoking policies

By Jim Dryden

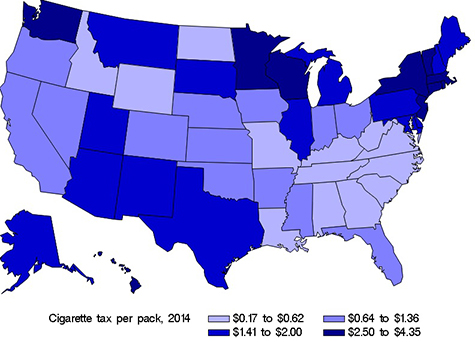

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine found that suicide rates declined in states that implemented higher taxes on cigarettes and stricter policies to limit smoking in public places. They also noted an increase in suicide rates in states that had lower cigarette taxes and more lax policies toward smoking in public. The map displays the range of state cigarette taxes from the lowest (lightest blue) to the highest (darkest blue).

Cigarette smokers are more likely to commit suicide than people who don’t smoke, studies have shown. This reality has been attributed to the fact that people with psychiatric disorders, who have higher suicide rates, also tend to smoke. But new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis finds that smoking itself may increase suicide risk and that policies to limit smoking reduce suicide rates.

In a study published online July 16 in the journal Nicotine & Tobacco Research, a team led by Richard A. Grucza, PhD, reports that suicide rates declined up to 15 percent, relative to the national average, in states that implemented higher taxes on cigarettes and stricter policies to limit smoking in public places.

“Our analysis showed that each dollar increase in cigarette taxes was associated with a 10 percent decrease in suicide risk,” said Grucza, associate professor of psychiatry. “Indoor smoking bans also were associated with risk reductions.”

Grucza’s team analyzed data compiled as individual states took different approaches to taxing cigarettes and limiting when and where people could smoke. From 1990 to 2004, states that adopted aggressive tobacco-control policies saw their suicide rates decrease, compared with the national average.

The opposite was true in states with lower cigarette taxes and more lax policies toward smoking in public. In those states, suicide rates increased up to 6 percent, relative to the national average, during the same time period. From 1990 to 2004, the average annual suicide rate was about 14 deaths for every 100,000 people.

“States started raising their cigarette taxes, first as a way to raise revenue but then also as a way to improve public health,” Grucza explained. “Higher taxes and more restrictive smoking policies are well-known ways of getting people to smoke less. So it set a natural experiment, which shows that the states with more aggressive policies also had lower rates of smoking. The next thing we wanted to learn was whether those states experienced any changes in suicide rates, relative to the states that didn’t implement these policies as aggressively.”

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2010, nearly 40,000 people died of suicide across the nation.

Every death that occurs in the United States is recorded in a database managed by the National Center for Health Statistics. Grucza’s team classified each suicide death based on the state where the victim had lived, as well as how aggressive that state’s tobacco policies were.

Using statistical methods, the researchers compared rates of suicide in states with stricter tobacco policies to rates in states with more lenient laws and lower taxes. They also determined whether people who had committed suicide were likely to have smoked. They learned that suicide risk among people most likely to smoke was associated with policies related to tobacco taxes and smoking restrictions.

“If you’re not a smoker, or not likely ever to become a smoker, then your suicide risk shouldn’t be influenced by tobacco policies,” Grucza said. “So the fact that we saw this influence among people who likely were smokers provides additional support for our idea that smoking itself is linked to suicide, rather than some other factor related to policy.”

Grucza

Although scientists have known for years that people who smoke have a higher risk for suicide, they had assumed the risk was related to the psychiatric disorders that affect many smokers. These new findings, however, suggest smoking may increase the risk for psychiatric disorders, or make them more severe, which, in turn, can influence suicide risk.

“We really need to look more closely at the effects of smoking and nicotine, not only on physical health but on mental health, too,” Grucza said. “We don’t know exactly how smoking influences suicide risk. It could be that it affects depression or increases addiction to other substances. We don’t know how smoking exerts these effects, but the numbers show it clearly does something.”

He explained that many states still have low cigarette taxes, while other states haven’t adopted comprehensive smoke-free air policies. Grucza predicts that if these states raise their cigarette taxes and restrict smoking in public, their suicide rates likely would fall.

Grucza suspects nicotine may be an important influence on suicide risk. Based on the study’s results, he said he is concerned that many new restrictions on public smoking don’t cover newer e-cigarettes, which deliver nicotine but release vapor rather than smoke. This mechanism purportedly allows those addicted to nicotine to get a “fix” without affecting the air others breathe.

“Nicotine is a plausible candidate for explaining the link between smoking and suicide risk,” Grucza said. “Like any other addicting drug, people start using nicotine to feel good, but eventually they need it to feel normal. And as with other drugs, that chronic use can contribute to depression or anxiety, and that could help to explain the link to suicide.”

Smoking and suicide rates

The research was funded by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), both part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additional funding was provided by the American Cancer Society. NIH grant numbers R01 DA031288, R01 DA026911, T32 DA07313, K01DA025733, P01 CA89392, U01 154248.

Grucza RA, Plunk AD, Krauss MJ, Carazos-Rehg PA, Deak J, Gebhardt K, Chaloupka FJ, Bierut LJ. Proving the smoking-suicide association: Do smoking policy interventions affect suicide risk? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, published online July 16, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.