By Jim Dryden

Laws designed to help teens safely ease into full driving privileges are linked to lower rates of teen alcohol use and binge drinking. States with stricter graduated driver licensing (GDL) laws not only have less drinking and driving among teens, but less alcohol consumption by teenagers. (Photo: E. Holland Durando/School of Medicine)

State laws designed to help teens gradually ease into full driving privileges may have an unintended effect: lowering rates of teen alcohol consumption and binge drinking.

In states with stricter graduated driver licensing (GDL) laws, there is not only less drinking and driving among teens, but less alcohol consumption by teenagers, according to new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The findings are published in the May issue of the journal Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research.

“We found that when driver licensing laws are more restrictive, kids tend to drink less,” said first author Patricia A. Cavazos-Rehg, associate professor of psychiatry. “The laws provide rules and a structure that encourage better behavior rather than punishing bad behavior. These laws are very specific about what kids should and should not be doing.”

GDL laws are designed to make the roads safer, especially for teen drivers. In 2012, the most recent year for which statistics are available, 184,000 young drivers were injured in crashes, and 23 percent of those drivers had consumed alcohol.

The Washington University research team analyzed data from more than 129,000 high school seniors who answered questions about substance use as part of the Monitoring the Future study. The annual, national survey has been gathering data from students since 1975. For this study, the researchers analyzed drinking-related data for the years 2000-13.

Forty-five percent of high school seniors reported drinking within a month’s time of when they’d been surveyed, and 26 percent reported binge drinking — consuming at least five drinks on one occasion — within the previous two weeks.

Seventeen percent said they had ridden in a car with a driver who had been drinking; nearly 12 percent reported that in the previous two weeks, they had driven after drinking; and 7 percent reported having driven after binge drinking.

But as states have placed more restrictions on teen drivers, those numbers have declined. Teens have become less likely to report any drinking behaviors if from a state with a GDL law rated as good. The laws are scored according to the types of restrictions placed on younger drivers, including limits on the number of passengers such drivers may transport and how late at night they are allowed to drive. The restrictions in the various state laws were assigned points; the more points a law received, the better the law was rated.

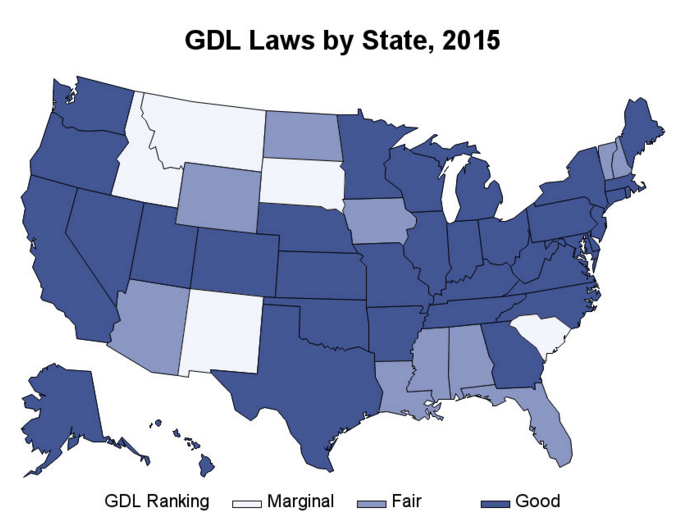

The scoring system was developed by the International Institute for Highway Safety, which ranks the various GDL laws as good, fair, marginal or poor. As of 2015, 35 states had GDL laws ranked as good. Another 10 states’ laws were rated fair, and five were considered marginal. More than half of the students in the study lived in states with “good” GDL laws.

Compared with teens from states with laws rated as good, respondents from states with marginal or fair laws were about 35 percent more likely to report riding with a driver who had been drinking or even binge drinking, and about 40 percent more likely to drive after drinking themselves.

Using statistical methods, the researchers also determined that drinking and driving was less common in states with stricter GDL laws, as was binge drinking and frequent alcohol consumption completely apart from driving.

Cavazos-Rehg said the laws not only appear to be having an impact now but may for years to come. When people drink early in life, she explained, many develop alcohol-related problems later, so, since stricter GDL laws are related to less drinking, they also may lead to fewer problems with alcohol abuse and dependence down the road.

“Not only could these laws have short-term benefits, they could help improve lives over the long haul,” Cavazos-Rehg said. “Even if these effects weren’t intended, we know that the earlier drinking behaviors begin, the higher the likelihood those behaviors will transition into addiction.”

In 2015, the International Institute for Highway Safety, which ranks the various graduated driver licensing (GDL) laws, listed 35 states as having good GDL laws. Another 10 were rated fair, and five were considered marginal. More than half of the students surveyed in the study lived in states with “good” GDL laws. (Image: Patricia Cavazos-Rehg)